Rangefinder

Magazine

May 2004

This article was originally published at: http://www.rangefindermag.com/Magazine/May04/singer.tml

Profile: Robert J. Kelly by Larry Singer

The Search for Sweet Light

The photographic creations of Robert J. Kelly, which have hung, and are currently displayed in some of the most prestigious galleries in the United States, are in many ways similar to Kelly himself. Both Kelly and his photography speak softly yet clearly, and both are intensely introspective and purposefully precise.

The photographic creations of Robert J. Kelly, which have hung, and are currently displayed in some of the most prestigious galleries in the United States, are in many ways similar to Kelly himself. Both Kelly and his photography speak softly yet clearly, and both are intensely introspective and purposefully precise.

Art gallery owners have said of Kelly that he paints with a camera far more beautifully than most artists with a brush. Although technically of a highly realistic nature, Kelly’s evocative images capture the range of artistic feeling most often attributed to the French Impressionists. From the vivid colors of a Chilean cityscape to the subtle hues of a Swiss meadow, Kelly sees subjects with a painter’s sensitivity enhanced by superior, state-of-the-art technical skills.

The quality that differentiates Kelly’s output from others in the world of art photography is his ability to consistently transcend the two-dimensional limitations inherent in his craft.

At a young age, Kelly’s artistic sensibilities rose to the surface, as evidenced by his early sketches of horses and caricatures. “When I was 19 years old, I went to Europe with my cousin,” explains Kelly, 52, about his introduction to, and eventual seduction by, photography. “While there, I picked up my first camera, an Olympus, and I really liked the immediacy of it. Then, when I got in the darkroom and experienced the magic of watching the image emerging in the developer, I was hooked.”

Early in his career, well before he gained substantial fame and a national following, Kelly studied under the direction of master photographic craftsmen who would alter the direction of both his work and his life.

Early in his career, well before he gained substantial fame and a national following, Kelly studied under the direction of master photographic craftsmen who would alter the direction of both his work and his life.

“I went to the Winona School of Professional Photography,” he says, “and oddly enough, I had my first picture published in Rangefinder back in the ’80s. It was a picture I during a workshop with Gary Bernstein.

“I also went up and studied several times at Rockport at the Maine Photographic Workshops. I studied with Ted Orland and Dan Anderson, who had printed with Ansel Adams and Bernie Meyers—who was one of the top Cibachrome printers at the time.

“It was a very cool school because they basically had some of the best working photographers in the world come in, and you could sit and eat with them and pick their brains and study with them for two weeks at a time.”

It was Linda Lapp, a portrait photographer, however, who, Kelly reveals, had the most profound influence over his work, and eventually, his career. “She taught me,” he says, “to look at the quality of light first and the subject second. As soon as I wrapped my brain around that concept, my photography really took off to a different level. I now consider myself a light catcher.”

|

|

|

Another of Kelly’s primary influences is a man who even today sets the standard in environmental photography. “I really love the landscapes of David Muench,” Kelly says. “He just blew me away with his photographs. I learned a lot from him and tried to implement some of his technique when I went to Death Valley. I thought it was a successful trip because I caught ‘David Muench light’ in my scenes.”

It is this light, this “sweet light,” as Kelly refers to it, which sets his work apart.

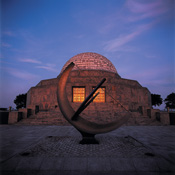

Describing sweet light, Kelly says, “In Europe they call it ‘even fall.’ Here they call it ‘magic light’ or ‘sweet light.’ It’s usually found at the beginning or end of the day when the contrast is lower, as opposed to midday when the contrast is at its most extreme with extremely harsh shadows. I just like the subtlety. Also, I think it’s that one particular moment when you get luminosity from everything that you don’t get at any other time in the day. There’s a glow to it, and that’s basically what I try to catch.”

Although Kelly’s work is frequently described in metaphysical terms, this quality is not something Kelly tries to achieve intentionally.

|

|

|

“I think it’s unconscious,” he says. “First, I look for moments of magic in the light, and then I look for taking the simple and making it extraordinary. I think it’s light that makes my work distinctive, and that light produces a more painterly approach to composition—as opposed to me just documenting a scene. Without that light, it’s nothing.

“I‘ve been very mindful of designing my life and purpose in that I want to give a moment of peace to someone. The best way I can describe my motivation is through the words of a character in the old television program “Car 54, Where are You?” In “Car 54,” Toody, the police officer, would go, ‘Ooh, ooh.’ When I look in my viewfinder and go ‘ooh,’ and then someone stands in front of my work and goes ‘ooh,’ that’s what I am going for.

“There has to be some sort of transcendent quality to my photographs, whether it’s spiritual, emotional, psychological or humorous. It has to have that transcendent quality for me to feel successful with the image.”

|

|

|

As most photographers who attempt to transition into the world of art photography, Kelly first toiled in the field of commercial photography, but did so on a consciously limited basis.

“When it came to commercial photography, I did anything I had to, but just enough of it to pay for equipment and photographic junkets,” says Kelly, who now resides in Lake Forrest, Illinois. I did everything from ads for Olson rugs to head shots for actors and models. I also went into a partnership with a guy who owned a studio, and I did a lot of tabletop stuff.”

Kelly is a man who methodically sets personal and professional goals. “When my daughter was born,” Kelly, who at the time owned a sign company, says, “I set my sights on being a full-time professional photographer by the time she was 10, and I beat that projection by three years. I think she was seven when I was doing photography full time. So it was a slow, but steady transition into photography over a five- to seven-year period.”

Early in his career, when attempting to use materials that would give his images the greatest degree of permanence, Kelly discovered Cibachrome. Today, Kelly considers himself a printmaker, constantly experimenting with the latest technology in order to produce an exceptional final image. “For example,” he says, “I can now make prints using the Giclee method on watercolor paper, canvas or silk. The possibilities are endless.”

To initially capture his images, Kelly now uses both 35mm and medium format cameras, as well as state-of-the-art digital gear.

To initially capture his images, Kelly now uses both 35mm and medium format cameras, as well as state-of-the-art digital gear.

“I started out with an Olympus, Kelly says, “and then went to Contax. From there I started using Nikon gear and Hasselblad. For the last four years I’ve been shooting all my work with a Nikon digital D1X.

“I’ve always done things a little differently,” Kelly explains, “even when I shot on traditional film. I would have my lab scan my 35mm and medium format images and convert them to digital. I would then do all the color correcting and contrast control in that process and create a new file, color and contrast corrected, onto an 8x10 transparency. I would then print that larger image onto cibachrome material. It gave me the vibrancy and luminosity I was looking for. I also decided to do Cibachrome printing because I wanted to make a statement that would last. At that time only Cibachrome or dye transfer offered the longevity and color brilliance I wanted.”

This labor-intensive and rather expensive technique allowed Kelly to produce images up to 85 inches for display, such as those now hanging in the Gallery Sur in California—a salon with which he has been associated since 1991.

“I never really concentrated on getting into galleries,” Kelly says. “In the early and mid 1990s I went out and did 30 to 35 fine art shows a year in Colorado, Chicago and Florida. So I would do the art shows every year and different galleries would pick me up along the way.”

With the profit from his photography, Kelly needs to be self sustaining. However, this has been, for Kelly, a long-term project. “Basically it’s been a lengthy process to get to a place where I could actually make money doing photography exclusively,” Kelly says.

With the profit from his photography, Kelly needs to be self sustaining. However, this has been, for Kelly, a long-term project. “Basically it’s been a lengthy process to get to a place where I could actually make money doing photography exclusively,” Kelly says.

Traveling extensively, Kelly has cultivated his sensitivity to the quality of sweet light. His images of Maine’s rugged coastline and the stark realities of Death Valley reflect his appreciation and understanding of light as the very essence of fine art photography. He has brought that same sensitivity to his Chicago portfolio recently commissioned by Storck USA, L.P., a German-owned, Chicago-based company.

Gallery owner Richard Harshman explains some of the reasons for Kelly’s wide-ranging appeal: “Kelly’s images capture the romantic, the mystical and the dramatic. They wake the special character of expansive landscapes with skill and sensitivity. He captures endless horizons, enormous skies and the immense changes in atmospheric conditions, which lead to subtle shifts in color and in scale perfectly.

“His use of color is superb,” Harshman continues, “and his sense of form and texture are especially effective. Light strikes the various planes, and his images become three-dimensional. His photographic images stimulate thought, tease the imagination, and even create a mood of personal reflection and meditation.”

When it comes to defining art photography, Kelly says in the final analysis, what he tries most to capture on film is “a moment of peace that allows those who see my work to experience the power of nature to rejuvenate spiritually. It also has to have a universal and timeless quality. I consider a photograph truly successful when it energizes the soul, if only for a time, and for that moment removes us from all social burdens.”

When it comes to defining art photography, Kelly says in the final analysis, what he tries most to capture on film is “a moment of peace that allows those who see my work to experience the power of nature to rejuvenate spiritually. It also has to have a universal and timeless quality. I consider a photograph truly successful when it energizes the soul, if only for a time, and for that moment removes us from all social burdens.”

Robert Kelly can be reached by email at: footprints@robertjkelly.com, or by visiting his web site: robertjkelly.com.

ALL IMAGES COPYRIGHT © 2004 ROBERT J. KELLY

Larry Singer is a former newspaper writer and photographer now living in Lauderhill, Florida. He has taught photography in Florida and Denver and now has an obsession with hearts. He can be contacted at larrysinger@mac.com.